One of the most important outcomes for academy students is self-agency. In concrete terms, agency means that students have the belief that they can positively affect their lives and possess the skills to do so. Student agency should be addressed in a comprehensive fashion starting with developing a shared vision at the school level.

An academy should operate from a shared vision that highlights student agency. Initially, a shared vision can be generated by faculty and staff.

Faculty and Staff Shared Vision

Faculty and staff can engage in an abbreviated version of the shared vision in which the larger community can be asked to participate at a later date (see the section below entitled Expanding the Shared Vision).

The process begins by asking faculty and staff to answer the following questions:

-

According to current test scores, how are our students doing?

-

What happens to our students once they leave our K-12 system?

-

Why do we come to school? Why is school important?

-

What do we want our students to know and be able to do?

-

What does a successful student look like?

-

What does an ideal school look like, feel like, and prioritize?

Faculty and staff can be asked to answer these questions individually and then share out in small groups. Common themes should be identified and these themes prioritized.

The process should culminate in a relatively succinct statement like: Students will become lifelong learners in a supportive and inviting environment that promotes individual learning and teamwork.

Expanding the Shared Vision

If time and resources allow, input for a shared vision should be elicited from all members of the school community—administrators, teachers, nonteaching staff, parents and guardians, students, business representatives, and community members.

Creating a shared vision involves six crucial steps: (1) identify stakeholder groups, (2) create guiding questions to generate input, (3) gather input from stakeholder groups, (4) prioritize and synthesize input, (5) take a final vote, and (6) deploy the shared vision.

Step 1: Identify Stakeholder Groups

Because the overall goal of a shared vision is to include the perspectives of each stakeholder, it is important to engage as many voices from as many diverse groups as possible. When all stakeholders are invited, supported, and heard, there will be many people dedicated to doing the hard work required to achieve the vision. As mentioned, stakeholders to consider including in the shared vision process are: certified staff (teacher aides, maintenance, custodial, cafeteria, transportation, health, clerical, and administration staff), students, parents and guardians, community members, and representatives from local businesses.

Step 2: Create Guiding Questions to Generate Input

Essential questions help to guide productive discussions about the work of creating a shared vision. Participants should be encouraged to share experiences and opinions, explore ideas, and address assumptions and preconceived notions about the workings of the school in general. This includes discussions about the school’s current vision (if one exists), how teaching and learning happen, what knowledge and skills students are currently obtaining, and what students need to be successful in the future. Questions like those listed above might be asked:

-

According to current test scores, how are our students doing?

-

What happens to our students once they leave our K–12 system?

-

Why do we come to school? Why is school important?

-

What do we want our students to know and be able to do?

-

What does a successful student look like?

-

What does an ideal school look like, feel like, and prioritize?

Step 3: Gather Input From Stakeholder Groups

The next step in creating a shared vision is focused on gathering relevant input from stakeholders through hosted conversations. Hosted conversations are separate, facilitated meetings for specific stakeholder groups. Separate meetings are held for different stakeholder groups in order to maximize information gathered specific to their perspectives and needs. All meetings should be held within a short time frame to ensure that schools receive maximum input from stakeholders before a loss of momentum for creating the vision occurs.

Step 4:Prioritize and Synthesize Input

The goal of this step is to review and synthesize all gathered input. Initially, a school team should be identified to asses all input. This group can be comprised of any invested stakeholders. The team then uses a process (such as the affinity diagram process) to combine similar ideas and create categories based upon the types of ideas (for example, environment, academics, character). Once general categories are created, the team can work to narrow the ideas and discover the overall concept that represents various ideas. With clear, distilled information, the team can create several examples of vision statements that reflect the concepts and ideas discussed. Ideally, the vision will be captured in one to two sentences.

Step 5: Take a Final Vote

When a set of possible shared vision statements is complete, stakeholders must be assembled again in order to seek input and continue building a community of purpose and collaboration. This step includes critical elements of facilitation. Specifically: remind participants of the process used to gather input, describe with transparency how the initial stages of input gathering led to the statements of a shared vision (describe the work of the team), and help participants identify and embrace the roles they will assume in achieving the chosen shared mission.

Step 6: Deploy the Shared Vision

When a vote has determined the final shared vision, all stakeholders should be notified. Team members and school participants should be available to help communicate the vision process and the vision statement whenever possible. A shared vision is best communicated using multiple formats. For example, graphics, newsletters, social media outlets, and in-person meetings can all be used to communicate the vision statement. Once the vision has been established and communicated, it should guide decision-making and bring clarity to setting strategic goals, objectives, and outcomes.

Translate a Shared Vision Into Classroom Level Goals

The school-wide vision should be translated into a more classroom-specific version by the teacher and students. This should occur in each homeroom (or some equivalent to a homeroom) so that each student engages in the process only once.

To illustrate this process, reconsider the shared vision described previously: Students will become lifelong learners in a supportive and inviting environment that promotes individualized learning and teamwork. This type of vision is typical at the elementary level. At the secondary level shared visions like the following are more common: Students will engage in work they are passionate about to develop the knowledge, skills, and habits of mind necessary to succeed in college and career, overcome obstacles to their well-being, and contribute positively to their communities.

In their homeroom classes, students, guided by teachers, would attempt to translate the school-wide vision into class level behaviors. This process is facilitated by questions posed by the teacher. For example, for the elementary shared vision the teacher might ask the following questions:

-

How do supportive students act, think, and feel?

-

How do team players act, think, and feel?

-

What qualities do lifelong learners have?

-

What words describe the qualities that would best help us reach our goals this year?

For the shared vision at the secondary level the teacher might ask the following questions:

-

What metacognitive skills do we need to develop so that we can do our best?

-

What are the qualities of good collaborators?

-

What habits do we need to develop to be successful beyond high school?

Student answers to the questions should result in concrete protocols like the elementary code of conduct in figure 8.1.

Figure 8.2 contains examples at the secondary level.

Keeping Track of Progress

Individual classes can develop rubrics that can be used to measure their progress. For example, figure 8.3 contains a rubric for self-control.

Finally, students as individuals and the class as a whole can maintain their progress using tracking systems like that in figure 8.4.

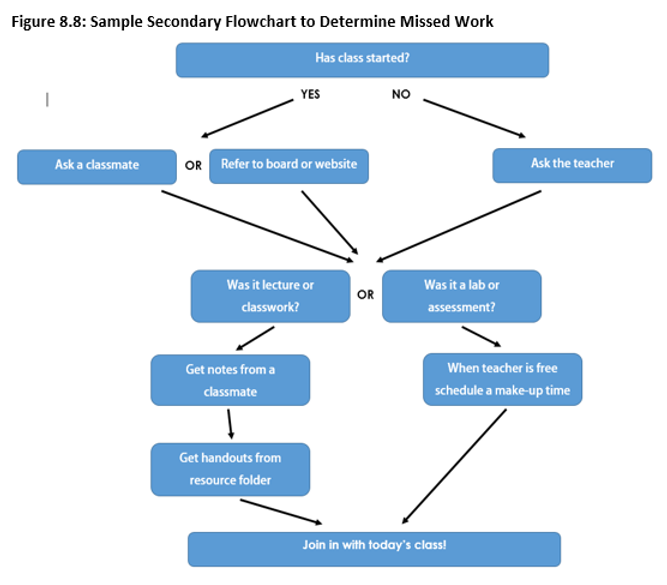

Creating Standard Operating Procedures

Standard operating procedures (SOPs) are individual sets of detailed instructions that help students consistently succeed in independently achieving goals for routines and procedures. The teacher in an academy does not control the pace of the class, rather, students use SOPs as guides to move through the content on their own. In this system, students bear more responsibility for behaviors and actions. Additionally, students are expected to be aware of their performance levels on proficiency scales, and they are equipped to create plans to improve their performance. Developed SOPs give students explicit guidance and directions to assume responsibilities and achieve goals. Additionally, working in this manner helps students develop independence and agency, even in the primary grades.

Creating an SOP involves the following four steps:

-

Identify common inefficiencies that frequently require redirection, reminder, or more time than necessary.

-

Prioritize inefficiencies based on need.

-

Determine the complexity and type of procedure. Does it require a procedural list or a flowchart?

-

Develop schoolwide and classroom procedures with input.

As indicated in the four-step process, SOPs can be articulated as a procedural list or as a flowchart. There are a number of situations for which SOPs might be created. These include the following:

-

How to properly check out books

-

What to do when done

-

What to do when stuck

-

When to include peer or teacher conferencing

-

How to properly ask to get a drink

-

How to properly sign out for bathroom breaks

-

Learning center activities

-

Attend a writing, reading, or mathematics workshop

-

Define hallway expectations

-

Communicate expectations of group work

-

Get ready for and leave class

-

Learn to use computers or other devices

-

Troubleshoot common computer issues

-

Establish bus routines

-

Work in common areas

-

Eat in the cafeteria

-

Use equipment for special activities (physical education, science, music, art, and so on)

-

Access websites or digital resources

-

Log into the computer

-

Deliver a sincere apology

-

Use strategies for calming down

-

Develop routines for the playground or recess

-

Set goals

The following four figures represent a number of typical SOPs.

Voice

Academy teachers can and should provide students with opportunities to become essential members of the learning environment. This can be accomplished in part by providing students with opportunities give feedback on both academic and cultural aspects of the classroom. Such opportunities give students voice.

For example, academic issues frequently relate to class content and instruction. Students can provide feedback on various ideas including assessment, teacher instruction style, assignment types, unit organization, and learning topics. Teachers can demonstrate the importance of student voice by keeping track of student feedback over time (a quarter or semester). With this record, students and teachers can review feedback and note significant changes.

Cultural issues relate to student behavior and environment. Specifically, the classroom culture often reflects the values of the students and the teachers. In turn, this affects the students’ and teachers’ treatment of one another as well as the class’s overall approaches to achievement. Student feedback on how they perceive a classroom culture is important. For example, when asked what they believe the class does well and what the class can improve on, opportunities arise for students to contemplate which of their behaviors reflect the desired culture of learning and which behaviors can be improved. This group effort helps create a culture that is safe and productive for all.

There are a number of tools that provide voice, including the following.

-

Affinity diagram: The purpose of this diagram is to help students collect ideas and group them into categories. Once this is accomplished, students can prioritize and vote to narrow the list.

-

Digital platforms: There are a variety of digital platforms (Padlet, Edmodo, and so on) available for teachers and students to gather and share input from different members.

-

Parking lot: The parking lot (Langford, 2015) is typically divided into four categories that help teachers address both general issues and issues with a focused purpose. The categories are: (1) things that are going well ( symbolized by a +), (2) opportunities for improvement (delta or triangle symbol), (3) questions (?), and (4) ideas (use a lightbulb or lightning bolt).

-

Plus or delta: This tool is a simplified version of the parking lot. Students focus only on plusses (what is going well) and deltas (what needs improvement) regarding a current activity.

-

Exit slips: Offered in a variety of formats, exit slips or tickets are a chance to get individual feedback from all students on any topic. They can be used as a quick formative assessment of learning, a way to get input about the culture of the classroom, or a self-reflection on the day. Exit slips can be used to gather important data as unique issues arise.

-

Interactive notebooks: Interactive notebooks are primarily used as communication tools. They can promote a dialogue between students and teachers or parents and teachers.

-

Brainstorming: Brainstorming is a great tool to gather input. Generally, input is a gathered from a group (either verbally or in writing) in order to get as many ideas on a subject or topic as possible. However, teachers should always be sure to provide safe spaces for each student to contribute.

-

Class meetings: This structure can involve a formal approach as outlined by SOPs or it can be an informal affair. In either case, meetings are a chance for groups to gather and discuss problems, successes, needs, and solutions on a regular basis.

Choice

Voice and choice are often connected; however, there are important distinctions. While voice is focused on creating opportunities for input into cultural and academic issues, choice is focused on providing opportunities to select provided opportunities within the social, environmental, and learning domains.

The social domain is any situation where there is interaction with other people. On a small scale, this means students can be allowed to group themselves according to their goals or interests. On a larger scale, students group themselves based on common interests and design projects that take place in or outside the classroom. In the digital age, there are many opportunities for social interaction with people all over the world.

The environmental domain is any space where students are situated for learning. Physical spaces may be the classroom or any area within or around the school, but they may also be other physical environments that are involved during the learning process such as homes, offices or retail spaces, museums, or performance spaces. Virtual spaces are areas accessed through the use of technology. Spaces such as social media platforms or virtual worlds allow for information or ideas to be shared. Contrived environments may involve either physical or virtual aspects but are created for specific learning purposes, usually on a temporary basis. For example, if a mock trial is being conducted in class, the arrangement of the classroom might change or a digital space might be created that mimics necessary aspects of the lesson during a social studies unit. Teachers can incorporate choice by allowing students to vote or give input on the arrangement of the physical space of the classroom. Teachers may also allow students to choose the environments which will best support their individual projects.

The learning domain is any situation in which students may access, practice, or prove mastery of any knowledge or skill within the curriculum. Learning domains may be physical or virtual. For example, students may access information through their teacher or their peers either physically or virtually. They may also access physical or digital support materials and resources. They may practice and eventually prove mastery through any number of physical or virtual acts that serve as forms of assessment. One way that a teacher could incorporate choice into the learning domain is by allowing students to select which topic in a unit they would like to study first.

As with voice, there are a number of tools that teachers can use to provide choice.

-

Power voting: This tool can be used in a variety of circumstances and with a variety of formats, but the idea is to ask students to prioritize their vote by offering multiple votes to be used in the interest of the student’s beliefs or preferences. For example, in a tool called Spend a Dollar, students are given four votes, each worth $0.25. They might choose to spend their four votes all on one item of particular importance or spread their votes out amongst several items.

-

Choice boards: Choice boards are any game-style board that visualizes choice. Students can pick from a variety of choices offered. Choices can be based on preferences or on content. Boards can be customized to meet a variety of needs, such as homework options, covering standards or learning goals, and so on.

-

Choice menus: Choice menus are also designed to engage students in choice. For example, “appetizers” might be choices regarding introductory content or vocabulary words. “Main course” offerings might be choices relevant to proficiency-level content while “dessert” items can offer extra activities or extensions to help students extend learning in order to achieve a 4.0 scale score.

-

Preference surveys: Information about student interests and preferences for how they like to learn can be gathered easily through use of in class or take-home surveys. Group feedback or feedback on content can also be gathered using surveys.

-

Interactive activity charts: Students make choices by interacting with a physical or virtual chart that offers multiple options.

-

Digital platforms: Students utilize platforms such as TeacherTube, Safari Montage, or Khan Academy to access instruction or activities aligned with their target of study. In this manner students are able to choose which format and program works best for them.

-

Must-do and may-do lists: Students are given a set of choices, all of which appear on one of two lists. A must-do list covers the expectations all students must meet; the may-do list offers a variety of choices for after the must-do list has been accomplished.

-

Task cards: A task card lists a task or learning activity for students to complete that is associated with a score 2.0, 3.0, or 4.0 learning target from a specific proficiency scale.

-

A task card can simply provide short questions that help students with practice or recall of simpler tasks, or it can provide directions for a more in-depth task. A teacher can provide a set of task cards for proficiency scales that students are currently working on, and when students finish early or when they have independent working time, students can select a card that will assist them in review for an upcoming assessment. Task cards may be self-contained activities, or they may act as players in a larger assignment. Teachers can use task cards to guide students to outside or online resources as well. Additionally, cards can be used individually, within small groups, or within large groups. Finally, task cards can be labelled as challenge cards, for students who want ideas and activities to push themselves to achieve score 4.0 targets.

Authentic voice and choice invites students to take responsibility for their own learning. An atmosphere of voice and choice creates an atmosphere that is supportive and encouraging for an entire class or school.

Empower has the ability to poll learners.

When creating Playlists in Empower, one of the tool options is the Voice & Choice. This tool allows facilitators to create multiple learning opportunities and set how many of them students need to complete in that step of the learning.

For example, you might want students to read a Shakespearean Tragedy. In the example pictured here, students are offered rich activities based on several plays and asked to pick two to read and report on.

Fostering Student Expertise

One of the more powerful ways to foster student agency is to acknowledge and use student expertise on a topic-by-topic basis. This means that as students demonstrate proficiency on a specific topic by achieving score 3.0 status, they become local experts for that topic who can be called upon by their fellow students. To accomplish this proficiency scales should be posted on the walls so that all students can see them. Next to each proficiency scale should be a list of names for those students who have already demonstrated score 3.0 status or higher.

In addition, an SOP should be created and made visible for all students to see. The SOP would contain the steps students might take when they are having difficulty reaching a score 3.0 (i.e., proficiency) on a specific scale. Of course, the SOP would contain specific guidance as to how the “topic experts” might be used. The SOP should also contain provisions for making requests of those topic experts and what to do if a topic expert declines the request for help. This is depicted in figure 8.9.

In figure 8.9 students are provided with simple but useful guidance regarding how to use topic experts. For each proficiency scale an SOP can also be developed that helps students achieve score 3.0 status as depicted in figure 8.10.

The SOP provides explicit guidance as to how to achieve score 3.0 status.

Further Resources

Tutorial Videos

Print Resources

Personalized Competency Glossary

User Guide: Playlists

One-Sheet: Student Work

One-Sheet: Assigning Work

One-Sheet: Create Activities